Schubert

Tuesday 22nd May, sunny and breezy under clear blue skies, & much warmer, said to be reaching mid-twenties before the end of the week. Suddenly the gardens are in leaf from top to toe, the Christopher rose is in bloom, the big flowerbed is thick with columbines and foxglove spikes. Feeding mealworms could become an expensive hobby, the starlings (although national population horribly in decline) are still the voracious thugs-of-the-birdtable that they always were.

Tuesday 22nd May, sunny and breezy under clear blue skies, & much warmer, said to be reaching mid-twenties before the end of the week. Suddenly the gardens are in leaf from top to toe, the Christopher rose is in bloom, the big flowerbed is thick with columbines and foxglove spikes. Feeding mealworms could become an expensive hobby, the starlings (although national population horribly in decline) are still the voracious thugs-of-the-birdtable that they always were.A long time ago, a year ago, in Gabriel's last year at Trinity, I thought I would write here about modern composers, find out the (literary) lowdown about the authors of the music I kept hearing about, and became excited about by contagion. The Rest Is Silence (Alex Ross) kept me enthralled for weeks. Shostakovich, Stravinsky. We were to proceed backwards, through the game-changers (Ravel, Debussy), but it never happened, though I read the biographies and listened to the music. The moment had passed. What prodded me towards Schubert? It was returning to Thomas Mann, esp The Magic Mountain, a book I started and never finished when I was an undergraduate, a story that ends in the trenches, with, for our hero, the poignant tender resignation of Der Lindenbaum (the Lied that became a folksong) running through the foul din of battle.

Trouble is, there's not much of a literary lowdown to be found. All I knew was that "he was truly great, comes straight after Beethoven, & died young" & he mainly wrote songs, also piano sonatas people thought unplayable at the time, and one very famous symphony called The Unfinished (nb I come form Manchester, was often taken to Hallé orchestra concerts when young, & Sir Charles Hallé was, I now know, one of the few, an early adopter, hugely keen on the Schubert repertoire. Or I probably wouldn't even have known that much). The more you look for Schubert's music the more riches you find, but biography is thin. He was born in Vienna, of lower-middle class parentage, just before the turn of the nineteenth century, was a child when Napoleon was at the height of his powers, lived to be adolescent and young adult in the pleasure-loving and cultured capital of a small country much diminished in world (ie European) politics, and, after the excitement of the Revolutionary Wars, in the throes of a deep repression. He had friends, they drank (a lot), made merry and made music. His mother died when he was thirteen; he would have got married when he was 19, but the law said he had to prove he could support a household and that he couldn't do. He trained as a chorister, but that career ended like the careers of most boy choristers. He trained as a primary school teacher (his father was a school-master), but that didn't work out. He made a very decent name for himself (though not much of a living) as a songwriter, on the local, domestic music scene; he tried for years to forge a career in opera, but failed to gain a foothold, as everyone was mad for Rossini, while he favoured German opera & it seems he had an unfortunately short fuse besides: and he contracted syphilis when he was 26.

All the while, music was pouring out of him. He wrote one piece, he started another... Symphonies, chamber music, song-cycles, a mass of works, great and small, a whole catalogue of challenging, innovative, beautiful and powerful music. He was arguably the best ever interpreter of the Romantic school of German philosophy, not only the passion for the sublime, but the insistence that the study of interior experience is not a frivolous indulgence, but the source of all our knowledge of the world and of ourselves, that was later, rebranded as "psychology" to shape another century of European thought. But nobody really knew. When he died he'd just begun attract attention, and the line on Schubert, for long afterwards, was "what a shame, he could have written such great music". He'd already done it.

He lived in Beethoven's shadow, in the same city, without ever (it seems) having any direct contact with the great man, who died in 1827. He saw himself as the successor of the master he revered, a figure in the socially radical model Beethoven has just invented (I am no man's servant, I am Beethoven). But it was impossible, because Schubert wasn't a virtuoso performer. Far from it, he was (far as I can tell) no more than an ordinary domestic pianist. It's hard to achieve fame, when the route to celebrity is closed. Hard for him to get a proper job in the conservativbe musical establishment either: the odds and the trends, were not in his favour. What he could do was write music, all kinds of music, but this was a trap for his career, and his reputation after death. Publishing deals were awful and the demand (as even the greatest celebrities found to their cost) was for home entertainment, shortish pieces that could be played, preferably at sight, by the average ordinary music lover (comparable level of skill, ability to load an ipod with taste, ah well). So Schubert was a local hero, prolific producer of popular stuff, who struggled in vain to get published outside Vienna, and when he died, he was the tubby little man who wrote charming songs and piano duets for the masses. Which didn't sound like much of an oeuvre.

The irony is that this passionate back-bedroom fan-boy really was Beethoven's rightful heir, Beethoven and more, things Beethoven couldn't do; and how often does that happen? If he'd been taken seriously in life, his music would undoubtedly have lived in Beethoven's shadow too, and he'd have had different frustrations. As it is, Schubert's status is a controversy that never happened. There are passionate Schubertians, and he has a secure place in the repertoire, and there it lies.

When he'd recovered from the acute phase of the disease his health was poorish, but okay, for the last five years of his life. In October 1828, when he was thirty one, he was taken ill at a dinner party. A few weeks' later he was dead. His sudden death is held to be a puzzle, but given the many forms syphilis can take, and given the horrific, grotesque long-drawn out torture it could and can inflict on the way to killing

you (in the absence of antibiotics), I don't see any mystery, and you could say he got off lightly. The sublime, unbearable sadness of his late and greatest music, the intense poignancy in the happiest, is also held by some to be a puzzle, since what, in his uneventful, modest, lower-middle-class biography prepares one for such intensity? Well, I don't know. He knew his own worth (and he was dead right). He knew he'd contracted a shameful, hideous disease that was going to kill him by inches; that all his hopes were blighted, his chances of love and happiness destroyed. He "lived with death as a constant companion for five years", and came to terms with this dark angel, faithful friend, in the language of a composer of genius. What does his class background, and failure to play before the Crowned Heads of Europe have to do with it?

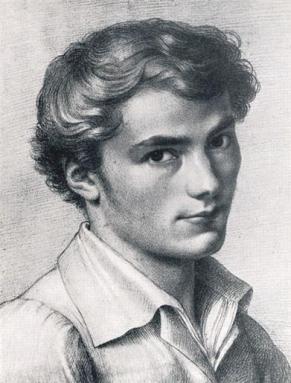

you (in the absence of antibiotics), I don't see any mystery, and you could say he got off lightly. The sublime, unbearable sadness of his late and greatest music, the intense poignancy in the happiest, is also held by some to be a puzzle, since what, in his uneventful, modest, lower-middle-class biography prepares one for such intensity? Well, I don't know. He knew his own worth (and he was dead right). He knew he'd contracted a shameful, hideous disease that was going to kill him by inches; that all his hopes were blighted, his chances of love and happiness destroyed. He "lived with death as a constant companion for five years", and came to terms with this dark angel, faithful friend, in the language of a composer of genius. What does his class background, and failure to play before the Crowned Heads of Europe have to do with it?(The portrait at the top of this entry is the standard model. The one on the right at the bottom is a disputed sketch of Schubert at 16. See here http://www.last.fm/music/Franz+Schubert/+images/2490089 (scroll down the comments, until you get to the informed response, which is the long one). Who can tell? I've looked at the two faces side by side, I think it could well be him).

His last sonata, in B flat (D960) is my favourite piece of music.

File beside John Keats.

The biography I read was: Schubert, John Reed, Master Musicians series; OUP; series edited by Stanley Sadie. It's really more of a Schubertian handbook, best on dates and the catalogue, and critical examples. I'm not convinced there isn't a literary biography (debunking, revisionist or otherwise), and I have my eye on one, (http://www.amazon.co.uk/Franz-Schubert-Elizabeth-Norman-McKay/dp/0198165234/ref=tmm_hrd_title_0/278-6711434-1284028) but I've no idea if I'll get round to it.

Der Leiermann (linked through the keynote portrait) is sung by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau; piano, Alfred Brendel.