Messolonghi: A History Of Ideas

Another day, almost our last day in Greece, in the Sacred City of Messolonghi, Peter finally rebelled. He'd had enough of my latest wild goose chase, wanted to know why we had to stop for ten minutes, let alone spend the night, in this dump, flat as a pancake, sickly, glaring hot, unfriendly, nothing to see but a dreary great lagoon with litter bobbing at the shore; totally devoid of attractive features... I blame myself. To me it was so obvious that Messolonghi had to feature on the Roumeli tour, I'd forgotten to explain what we were doing. I'd also forgotten to give my patient companion proper warning that even I wasn't expecting to like the place, and he probably was not going to like it either. Maybe I'd been hoping that Messolonghi would beat the critics, but August is not its best month. This flat modern town is the reverse of picturesque, the downtown area is the only place on our whole trip where I felt a foreign woman should be uneasy alone, and there was a cockroach in the shower. Okay, the roach was dead, always the best kind, but even so...

Another day, almost our last day in Greece, in the Sacred City of Messolonghi, Peter finally rebelled. He'd had enough of my latest wild goose chase, wanted to know why we had to stop for ten minutes, let alone spend the night, in this dump, flat as a pancake, sickly, glaring hot, unfriendly, nothing to see but a dreary great lagoon with litter bobbing at the shore; totally devoid of attractive features... I blame myself. To me it was so obvious that Messolonghi had to feature on the Roumeli tour, I'd forgotten to explain what we were doing. I'd also forgotten to give my patient companion proper warning that even I wasn't expecting to like the place, and he probably was not going to like it either. Maybe I'd been hoping that Messolonghi would beat the critics, but August is not its best month. This flat modern town is the reverse of picturesque, the downtown area is the only place on our whole trip where I felt a foreign woman should be uneasy alone, and there was a cockroach in the shower. Okay, the roach was dead, always the best kind, but even so...Why are we here?

Good question...

Philip of Macedon's blitzkreig empire didn't last long. Philip got assassinated. Alexander went off on his own astonishing go for it until you got no armies left World Domination game, and basically never came back. The generals scrapped, the chain of command was broken, democracy had died and (for all democracy's many awful faults) permanent warfare proved an inefficient substitute: Greece ceased to be a great power. Macedonian rule had a late revival under Philip V, but then he unwisely backed Carthage against Rome. Things fell apart again, and the Romans, to cut a long story short, just walked in the back door as soon as they had a free moment (168 BCE).

The Greeks had huge cultural influence as Roman citizens. They went on doing pretty well in the time we call the Dark Ages, through the collapse of the Western Empire and for hundreds of years after that; off on their own prosperous and dazzling Byzantine track. But the Byzantine empire never recovered from the debacle of the Fourth Crusade. In 1453, Byzantium (aka Constantinople aka eventually Istanbul) fell to the Ottoman Turks. Arabic, Byzantine and nascent Western European scholars had been scouring lost libraries and inacessible lamasaries for shards of the old Greek magic since the fall of Rome, and piecing the fragments together. At the time when a new world civilisation, that endures, just barely, even to the present day, was rising from those magic shards, Greece itself fell off the map, and vanished.

There'd been other revolts, over the centuries. The War of Independence (1821) was different. The Ottoman Empire was dying, rotted from within. Primed by the success of (allegedly) egalitarian, idealistic revolutions in France and in the American colonies, the world was watching. Philhellenes of many lands, thrilled at the prospect of rescuing the Cradle of Civilisation, rushed to the barricades. Delacroix painted scenes of lightly draped, glamour-model carnage. George Gordon, Lord Byron, the famous poet, who'd found good copy and had a wonderful time around here, on his Grand Tour, (as Peter & I had seen memorialised, in Ali Pasha's citadel in Ioannina), offered his services. He arrived at Messolonghi, the rebel HQ, in January 1824, extravagently equipped with weapons, money, scarlet uniforms and gold braid. He was welcomed equally extravagently and set his considerable gifts to work, trying to organise some decisive action. He did not succeed. The freedom fighters were vain, venal, and quarrelsome as a sack of cats. The weather was awful, living conditions sodden and squalid. At just turned 36 Byron was not a young man (worn out by too much fun). He caught a fever and died, within a hundred days of his arrival, on 24th April. His intervention, and his death, had considerable effect on world opinion, and in Greece he is still regarded as a national hero. In 1827 the Greeks regained their independence: some would say for the first time since Cheronaea.

But that's only half the story, because I wasn't drawn to the idea, the romance of Greece, directly. I was never in that league. It's all second hand, a bag of scraps bequeathed to me by nineteen and eighteenth century schoolboys (and their sisters, who fed on the crumbs from that table), raised on those magic shards. We're here because the spartans on the sea-wet rock sat down and combed their hair, because Heracles wore the intolerable shirt of flame, that human power cannot remove...; because the real hero of Marathon deserved something better than fame, Name not the clown with these... because Keats hungered for "Tempe and the vales of Arcady", places that for him, as for me, lived entirely in the imagination... Cavafy's in there too, of course. The echoes and tags a writer follows, wanting to know the story. The Romantics and their interesting times, from whence I date my formation as a writer, when the world turned upside down...

And if it hadn't, I wouldn't be here. (I mean, someone like me just would not exist.)

At Messolonghi, with Byron (I've never rated his best-selling major works, but maybe I'll give Harold and Juan another look), the trails meet.

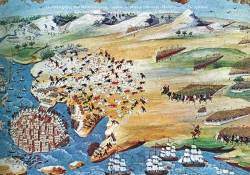

So, anyway, we visited the Byron room in the War of Independence museum in the Town Hall: inspected the plan of the great siege-battle and admired

the miniature cricket bat signed by a Notts County team; among other curious treasures. We made peace, walking in the quiet green Garden of Heroes, where the Philhellenes are buried, and found ourselves a better hotel. I think the naked young girl on Markos Botsaris's equivocal monument is meant to be Liberty? She's beautiful, anyway, and reminds me somehow of Neolithic Cycladean statuettes. If you ever visit Messolonghi, after I've talked it up so splendidly, go in Spring or Autumn. Check out the birdwatching and the mediaeval painted cave-chapels, and stay at the Liberty, opposite the Garden. It's a bit blockhouse-looking and drab, but fine indoors.

the miniature cricket bat signed by a Notts County team; among other curious treasures. We made peace, walking in the quiet green Garden of Heroes, where the Philhellenes are buried, and found ourselves a better hotel. I think the naked young girl on Markos Botsaris's equivocal monument is meant to be Liberty? She's beautiful, anyway, and reminds me somehow of Neolithic Cycladean statuettes. If you ever visit Messolonghi, after I've talked it up so splendidly, go in Spring or Autumn. Check out the birdwatching and the mediaeval painted cave-chapels, and stay at the Liberty, opposite the Garden. It's a bit blockhouse-looking and drab, but fine indoors.I'm very drunk, please could you get me a taxi?

Would you like to have sex?

I'm going to be sick!

So many graves. Back in Ioannina, on the nameless island in lake Pamvotida, I'd bought a "silver" pomegranate for eight euros. As you probably know, Demeter got her daughter back in the end, but Persephone, the Maiden, she who destroys the light by leaving us, has ever afterwards had to spend half the year in Hades, because she ate a handful of pomegranate seeds there. I didn't realise it at the time, but this symbol of life in death and death in life came to seem like the ideal souvenir.

Comments

Display comments as Linear | Threaded