I Walk Into The Picture

Thursday 8th September, cool and grey, glimpses of sun, the air outdoors heavy and humid, but no rain yet. The gale winds have died down completely now. There's been a bird singing, a robin I think, first birdsong in the garden for a long time.

Thursday 8th September, cool and grey, glimpses of sun, the air outdoors heavy and humid, but no rain yet. The gale winds have died down completely now. There's been a bird singing, a robin I think, first birdsong in the garden for a long time.In the last week of July, the night after the first of three alcoholic and carnivorous meals shared in Geneva, I slept uneasily and dreamed I was at a festival. It was in steep forest, the teepees, benders, tents, log huts, buried in bracken and mossy thickets along hillsides. I was looking for someone Norwegian called Anna Petersen (see what I did there, my husband is called Peter). I found her, dressed in pale blue denims: tall and slim, with black rough hair, white skin and blue eyes. She was some kind of leader of this politically engaged festival. She'd been trying to get in touch with Ax Preston, I was here to tell her that Ax Preston doesn't exist, he's a fictional character. And if you've read the books, I said, you'll know Ax didn't change the world, he didn't think that was possible, he only tried to change it, for a while. I'm not that kind of Utopian, I explained, like a child, absentmindedly dropping the make-believe. I'm afraid of that route. Ideally, I'd be trying to make the best world we can of what's already here, what's in us. But that's not what's happening now, it isn't what happened in the books. This is a time for saving what you can. The dream went off on a tangent after that. There were foxes, friendly little foxes in the tents with the people, and I copped a couple of flirty, definitely sexual advances (from men). I realised they didn't know how old I was, I didn't know what I looked like in this dream of course. Have you ever looked in a mirror in a dream?; I felt I ought to explain, only it was embarrassing.

Long afterwards, I realised the figure I called Anna Petersen had looked very like my best friend Mary Curran, only the Mary of a long time ago.

I rarely if ever dream about my fiction, in any shape or form, but I suppose I couldn't help it, in this summer without a summer. The faces of those children (adults really, but my son is twenty four, so children to me) lined up on the screen. Watching NASDAQ tumble, on the tv in the departure lounge at Gatwick, as I broke my non-flying vow -not really broke it, I'll fly for a serious family reason. Watching the fighting in the streets in Manchester, on another tv in an outrageous Celtic Tiger Years gin-palace of a bar in Peter's hometown, in the early hours.

My treat. If you write about full-on scifi disaster-futures (Nuclear Winter swallows us; Yellowstone blows its top; the Flood or the Ice Age engulfs us in an afternoon), I suppose you don't get these flashes, much less have them strengthen over years and years. My ruin was cumulative and slow, the Devil's work; not an Act Of God.

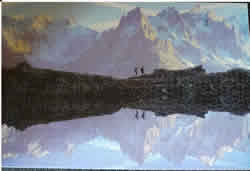

To get back to Les Aiguilles Rouges. The picture above is of me, unbelievably cold and wet, walking into my

jigsaw picture, sadly with zero co-operation from the weather around Mont Blanc. If you look carefully, you can see the glacier called the Mer du Glace, across the Chamonix valley, but of course no needles, and if there had been, they couldn't have been reflected in sunset or dawn light in the Cheserys lakelets. That would take very different timing. As it was, I was forced to pretend I was Tommy Voeckler, utterly determined to hang onto the yellow jersey one more time, to set a pace that got us back to La Flegere for the last telephorique down to the valley. One lives and learns. Next time, maybe.

jigsaw picture, sadly with zero co-operation from the weather around Mont Blanc. If you look carefully, you can see the glacier called the Mer du Glace, across the Chamonix valley, but of course no needles, and if there had been, they couldn't have been reflected in sunset or dawn light in the Cheserys lakelets. That would take very different timing. As it was, I was forced to pretend I was Tommy Voeckler, utterly determined to hang onto the yellow jersey one more time, to set a pace that got us back to La Flegere for the last telephorique down to the valley. One lives and learns. Next time, maybe. But the flowers were beautiful.

On the last evening, me very footsore with the trouble that's going to ground me completely one of these years, we took a short stroll up a tiny, raspberry dangling path between the chalets of Les Mousseaux to find John Ruskin's stone: Ruskin placed here in honour by local worthies on a great medallion set in a granite boulder, wood sorrel and wild strawberries clustering around it, under steep forest trees: really like the grounds of Brantwood, oddly enough. Looking remarkably rugged, wild haired and Beethovian, I must say. 1925. He loved Chamonix, of course. He'd hate it now, but he'd be wrong to get too upset, it's just like Cumbria. You don't have to go very far, to leave the crowds. We were alone most of the time.

On the last evening, me very footsore with the trouble that's going to ground me completely one of these years, we took a short stroll up a tiny, raspberry dangling path between the chalets of Les Mousseaux to find John Ruskin's stone: Ruskin placed here in honour by local worthies on a great medallion set in a granite boulder, wood sorrel and wild strawberries clustering around it, under steep forest trees: really like the grounds of Brantwood, oddly enough. Looking remarkably rugged, wild haired and Beethovian, I must say. 1925. He loved Chamonix, of course. He'd hate it now, but he'd be wrong to get too upset, it's just like Cumbria. You don't have to go very far, to leave the crowds. We were alone most of the time.Did someone say, yeah, well look at the weather you went out in...

You have a point.